Wystawa przeznaczona do oglądania na telefonach komórkowych.

Curatorial text, Mateusz Kokot

I'm not there now, an exhibition by Joanna Ambroz

Man needs not only the infallible posing of ultimate questions, but also the sense of what is feasible, possible, right here and now1.

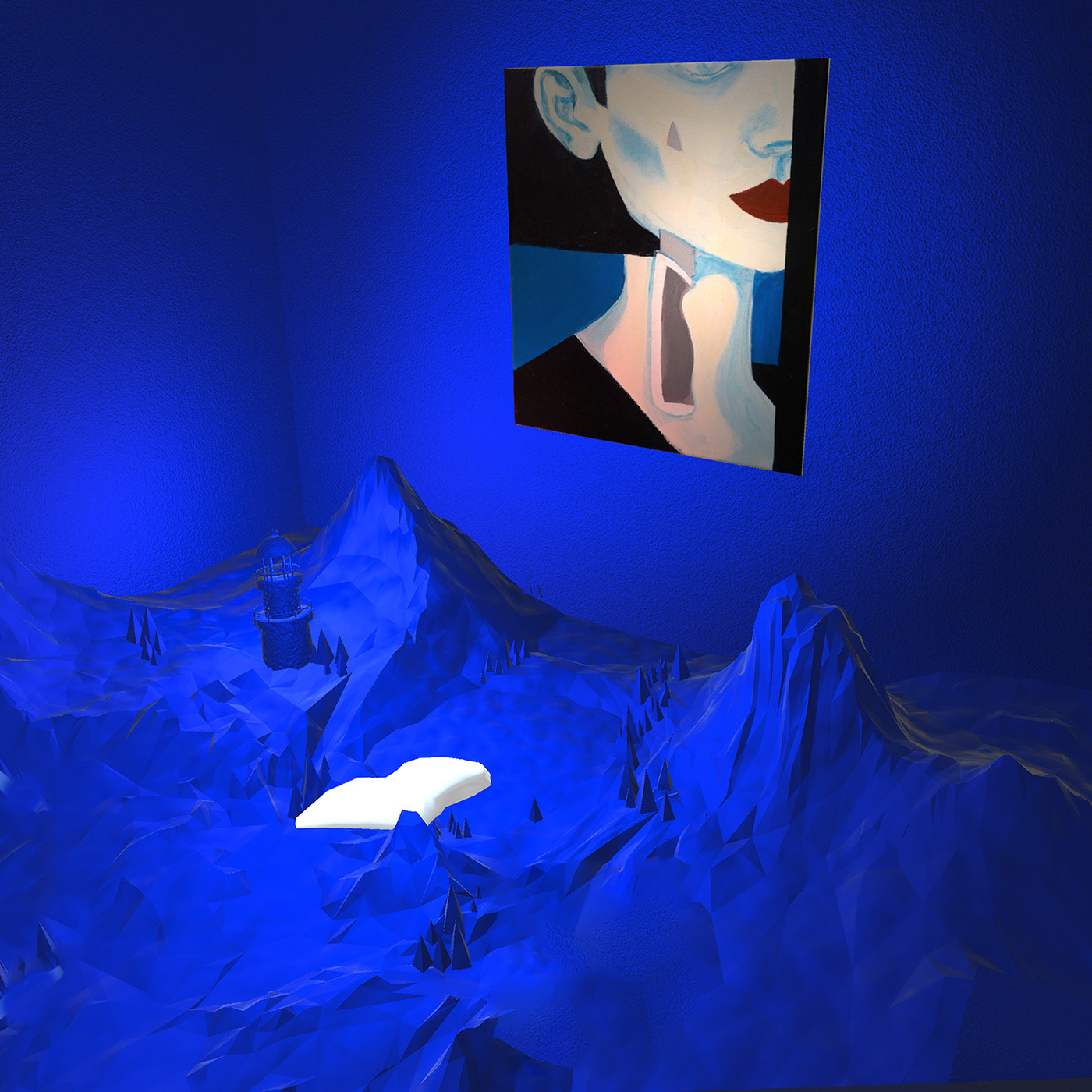

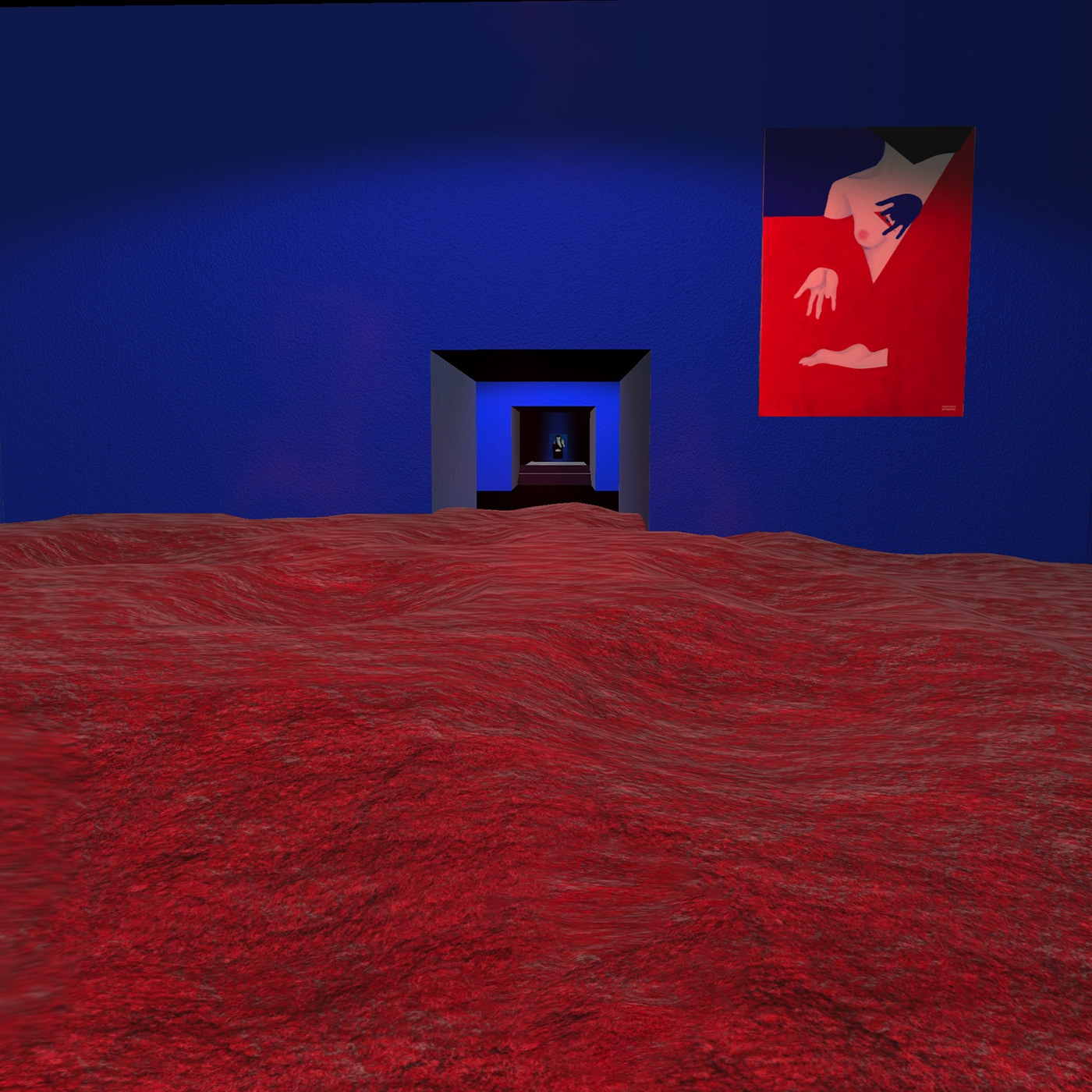

On March 29, 2020, Ambroz's mother passed away. In the painting Nothing Grows but Stings we see the artist's face, frozen in time, a month after the event. The dominant colors here are two: black and blue. The right eye, wide open, looks like the gaze of a statue. A gaze without a specific direction trapped in the inner and inaccessible world of the beholder. The left eye looks at the right eye. It is a tender observer; compassionate and desirous of understanding. This image is reminiscent of Pablo Picasso's 1904 painting Celestine. The monochromatic canvas is held in cool blues depicting the face of the owner of a house of shack in a Barcelona neighborhood, who has one blind eye.

In Ambroz's painting work, blue is not just an aesthetic choice. It is a symbol of mourning, but also of solace. A solid color, but also flexible and susceptible to change. The artist's image itself seems to show two facets. On the one hand, Ambroz looks at herself. On the other, like Tamara Lempicka, she wants to create herself anew. Her self-portrait is an area for personal stories. Stories of painful separations and constant moving as in the painting I need peace. Ambroz's experiences, beyond the personal dimension, are universal - present in the lives of most women. The paintings are mirrors in which the painter views herself. They reflect the period when she had to control her emotions. As the artist herself says - I have mirrors, because then I know that I am.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in one of her many lectures, said: Because when, at the end of life, we look back not so much on the good days that have passed, but precisely on the difficult ones, on life's storms, we see that they made us who we are today. Someone once said: »A stone thrown into a centrifuge comes out of it either grated to dust or polished.«"

Tekst kuratorski, Mateusz Kokot

Nie ma mnie tam teraz, wystawa Joanny Ambroz

Człowiek potrzebuje nie tylko nieomylnego stawiania ostatecznych pytań, ale również sensu tego, co wykonalne, możliwe, słuszne tu i teraz1.

29 marca 2020 roku odeszła mama Ambroz. Na obrazie Nic nie rośnie, a kłuje widzimy twarz artystki, zatrzymaną w czasie, miesiąc po tym wydarzeniu. Dominujące są tutaj dwa kolory: czarny i niebieski. Prawe oko, szeroko otwarte, wygląda jak spojrzenie posągu. Spojrzenie bez konkretnego kierunku uwięzione w wewnętrznym i niedostępnym świecie patrzącego. Lewe oko spogląda na prawe. Jest czułym obserwatorem; współczującym i pragnącym zrozumieć. Wizerunek ten przypomina obraz Celestyna Pablo Picassa z 1904 roku. Monochromatyczne płótno utrzymane w chłodnych błękitach przedstawiające twarz właścicielki domu schadzek w barcelońskiej dzielnicy, posiadającej jedno niewidzące oko.

W malarskiej twórczości Ambroz błękit nie jest jedynie wyborem estetycznym. Jest symbolem żałoby, ale także ukojenia. Barwą stałą, lecz również elastyczną i podatną na zmiany. Sam wizerunek artystki zdaje się ukazywać dwa oblicza. Z jednej strony Ambroz przygląda się sobie. Z drugiej, niczym Tamara Łempicka, pragnie stworzyć siebie na nowo. Jej autoportret jest obszarem dla osobistych historii.

Opowieści o bolesnych rozstaniach i ciągłych przeprowadzkach jak w obrazie Spokoju, czy ukazaniem hipokryzji na płótnie Kiedy praw kobiet bronią mężczyźni stosujący przemoc. Przeżycia Ambroz, poza wymiarem osobistym, są uniwersalne – obecne w życiu większości kobiet. Obrazy te są zwierciadłami, w których przegląda się malarka. Odbiciem okresu, w którym musiała kontrolować swoje emocje. Jak mówi sama artystka - Mam lustra, bo wtedy wiem, że jestem.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross w jednym ze swoich licznych wykładów mówiła: Bo kiedy pod koniec życia patrzymy wstecz nie tyle na minione dobre dni, ale właśnie na te trudne, na życiowe sztormy, widzimy, że to one uczyniły nas tym, kim dzisiaj jesteśmy. Ktoś kiedyś powiedział: »Kamień wrzucony do centryfugi wychodzi z niej albo starty na proch, albo wypolerowany«”2.

1Hans-Georg Gadamer, Prawda i metoda. Zarys hermeneutyki filozoficznej, przeł. Bogdan Baran, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa, 2004, s.17

2 Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, Życiodajna śmierć. O życiu, śmierci i życiu po śmierci, przeł. Malina Stahre-Godycka, Media Rodzina, Poznań, 2021, s. 13.

Kuratorstwo, projekt wystawy, muzyka: Mateusz Kokot